ST. JOHNSBURY, VT –

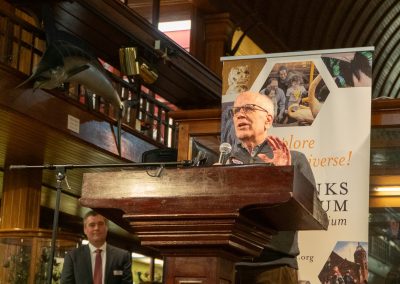

U.S. Senator Peter Welch (D-Vt.), Chair of the Senate Agriculture Subcommittee on Rural Development and Energy, celebrated the ribbon cutting for the Fairbanks Museum Science Annex with U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Deputy Under Secretary for Rural Development Farah Ahmad and local leaders. The project was funded in part by $2.5 million in Congressionally Directed Spending (CDS) for a USDA Rural Development (RD) Community Facilities grant secured by Senator Welch, along with a grant from the Northern Border Regional Commission (NBRC).

Founded in 1889, the Fairbanks Museum & Planetarium has been a cornerstone of St. Johnsbury for over 125 years. The museum’s Tang Science Annex is the first structure in Vermont to use the “mass timber” building technique, also known as cross-laminated timber (CLT), an innovative product that opens new markets for low-grade timber and reduces carbon footprints. The Science Annex is the first mass timber project funded by USDA.

“From the groundbreaking two years ago to today’s ribbon cutting, it’s been outstanding to watch the Fairbanks Science Museum Annex project be built from the ground up. Museums both reflect and shape our communities, and this project will serve as an investment not just in the future of the Fairbanks Museum, but in St. Johnsbury as a whole. This will showcase an innovative new use low-carbon timber product called mass timber—the first example of the product in Vermont and the first ever funded by the USDA—add an estimated 70 new jobs over the coming five years, and make science more accessible to all Vermonters,” said Senator Welch.

“This new science annex and renewal of the Fairbanks Museum will not only extend the museum’s natural science education in the 21st century, but will act as a catalyst for the renewal of St. Johnsbury, a town that first welcomed me to this country 75 years ago. I am so privileged to be in this public/private partnership with the USDA and Senator Welch in helping make this happen,” said Oscar Tang, philanthropist and retired financier.

Federal funding accounts for 55% of the total cost of the Science Annex project and was funded in part by Senator Welch’s FY22 Congressionally Directed Spending. Specifically, funding for this project comes through USDA’s Community Facilities (CF) program in addition to funding from the NBRC.